HORNET

The

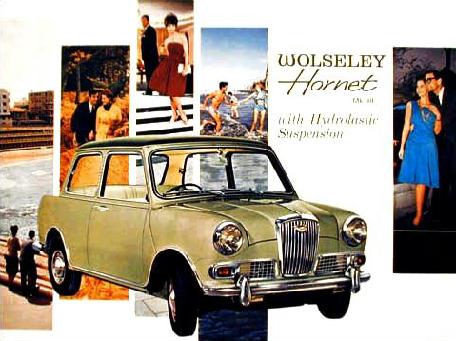

Wolseley Hornet 1960s model

An

upmarket version of the Mini

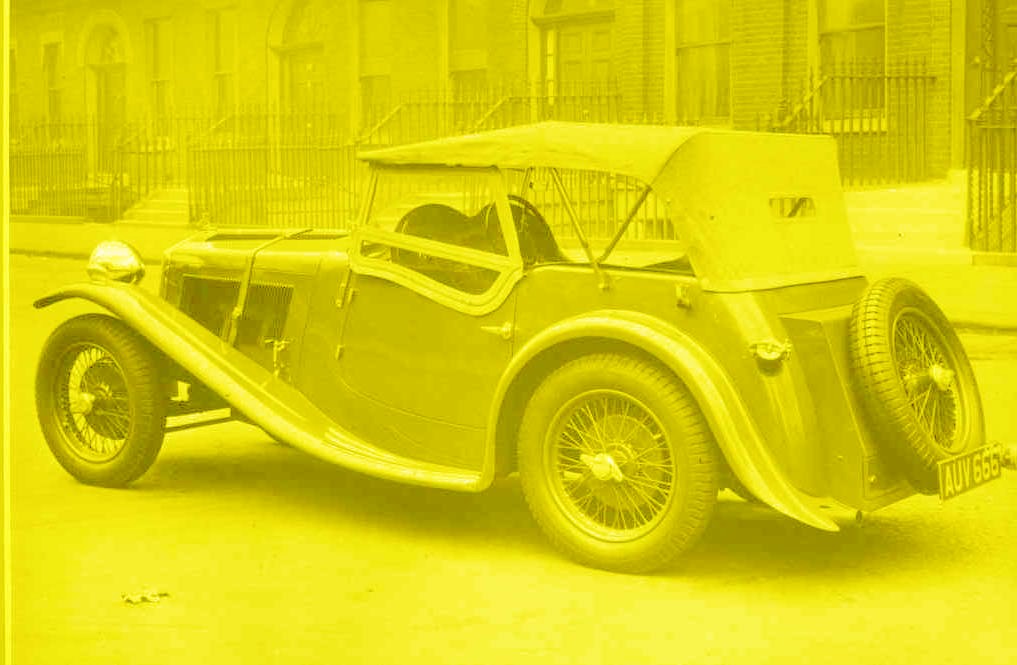

A

1930s Wolseley Hornet sports car

The

bodywork for these was made to order by a coachbuilder

of

the customer’s choice and there were many variations of this car.

The

series ran from 1930 to 1935

The Wolseley Hornet both in its 1930s sports

car

incarnation, and its 1960s posh mini version,

has

very little (in fact nothing) to do with

Theosophy

but we have found that Theosophists and new

enquirers do like pictures of classic cars

and we get a lot of positive feedback.

You can find Theosophy Wales groups

in

Bangor, Cardiff, Conwy & Swansea

Theosophy Wales has no controlling

body

and is made up of independent groups

________________________

The

Ancient Wisdom

by

Annie

Besant

Reincarnation

We are now in

a position to study one of the pivotal doctrines of the Ancient Wisdom, the

doctrine of reincarnation. Our view of it will be clearer and more in congruity

with natural order, if we look at it as universal in principle, and then

consider the special case of the reincarnation of the human soul.

In studying

it, this special case is generally wrenched from its place in natural order,

and is considered as a dislocated fragment, greatly to its detriment. For all

evolution consists of an evolving life, passing from form to form as it

evolves, and storing up in itself the experiences gained through the forms ;

the reincarnation of the human soul is not the introduction of a new principle

into evolution, but the adaptation of the universal principle to meet the conditions

rendered necessary by the individualisation of the continuously evolving life.

Mr. Lafcadio

Hearn ( "Mr. Hearn has lost his way in expressing – but not, I think, in

his inner view – in part of his exposition of the Buddhist statement of this

doctrine, and his use of the word "Ego" will mislead the reader of

his very interesting chapter on this subject, if the distinction between real

and illusory ego is not readily kept in mind.") has put this point well in

considering the bearing of the idea of the pre-existence on the scientific

thought of the West. He says: -

"With

the acceptance of the doctrine of evolution, old forms of thought crumbled ;

new ideas everywhere arose to take the place of worn-out dogmas ; and we now

have the spectacle of a general intellectual movement in directions strangely

parallel with Oriental philosophy. The unprecedented rapidity and multiformity

of scientific progress during the last fifty years could not have failed to

provoke an equally unprecedented intellectual quickening among the

non-scientific. "

"That

the highest and most complex organisms have been developed from the lowest and

simplest ; that a single physical basis of life is the substance of the whole

living world ; that no line of separation can be drawn between the animal and

vegetable ; that the difference between life and non-life is only a difference

of degree, not of kind ; that matter is not less incomprehensible than mind,

while both are but varying manifestations of one and the same unknown reality –

these have already become the commonplaces of the new philosophy."

"After

the first recognition even by theology of physical evolution, it was easy to

predict that the recognition of psychical evolution could not be indefinitely

delayed ; for the barrier erected by old dogma to keep men from looking

backward had been broken down. And today for the student of scientific

psychology the idea of pre-existence passes out of the realm of theory into the

realm of fact, proving the Buddhist explanation of the universal mystery quite

as plausible as any other."

"None

but very hasty thinkers,’ wrote the late Professor Huxley, ‘will reject it on

the ground of inherent absurdity. Like the doctrine of evolution itself, that

of transmigration has its roots in the world of reality ; and it may claim such

support as the great argument from analogy is capable of supplying."

(Evolution and Ethics, p. 61, ed. 1894 – Kokoro, Hints and Echoes of Japanese

Inner Life, by Lafcadio Hearn, pp. 237-39 london, 1896)."

Let us consider

the Monad of form, Âtma-Buddhi. In this Monad, the outbreathed life of the

LOGOS, lie hidden all the divine powers, but, as we have seen, they are latent,

not manifest and functioning. They are to be gradually aroused by external

impacts, it being of the very nature of life to vibrate in answer to vibrations

that play upon it.

As all

possibilities of vibrations exist in the Monad, any vibration touching it will

arouse its corresponding vibratory powers, and in this way one force after

another will pass from the latent to the active state. (From the static to the

kinetic condition, the physicist would say.) Herein lies the secret of

evolution ; the environment acts on the form of the living creature – and all

things, be it remembered, live – and this action, transmitted through the

enveloping form to the life, the Monad, within it, arouses responsive

vibrations which thrill outwards from the Monad through the form, throwing its

particles, in turn, into vibrations, and rearranging them into a shape corresponding,

or adapted, to the initial impact.

This is the

action and reaction between the environment and the organism, which have been

recognised by all biologists, and which are considered by some as giving a

sufficient mechanical explanation of evolution. Their patient and careful

observation of these actions and reactions yields, however, no explanation why

the organism should thus react to stimuli, and the Ancient Wisdom is needed to

unveil the secret of evolution, by pointing to the Self in the heart of all

forms, the hidden mainspring of all the movements of nature.

Having

grasped this fundamental idea of a life containing the possibility of

responding to every vibration that can reach it from the external universe, the

actual response being gradually drawn forth by the play upon it of external

forces, the next fundamental idea to be grasped is that of the continuity of

life and forms.

Forms

transmit their peculiarities to other forms that proceed from them, these other

forms being part of their own substance, separated off to lead an independent

existence. By fission, by budding, by extrusion of germs, by development of the

offspring within the maternal womb, a physical continuity is preserved, every

new form being derived from a preceding form and reproducing its

characteristics. ( The student might wisely familiarise himself with the

researches of Weissman on the continuity of germ-plasm.)

Science

groups these facts under the name of the law of heredity, and its observations

on the transmission of form are worthy of attention, and are illuminative of

the workings of Nature in the phenomenal world. But it must be remembered that

it applies only to the building of the physical body, into which enter the

materials provided by the parents.

Her more

hidden workings, those workings of life without which form could not be, have

received no attention, not being susceptible of physical observation, and this

gap can only be filled by the teachings of the Ancient Wisdom, given by Those

who of old used superphysical powers of observation, and verifiable gradually

by every pupil who studies patiently in Their schools.

There is

continuity of life as well as continuity of form, and it is the continuing life

– with ever more and more of its latent energies rendered active by the stimuli

received through successive forms – which resumes into itself the

experiences

obtained by its incasings in form ; for when the form perishes, the life has

the record of those experiences in the increased energies aroused by them, and

is ready to pour itself into the new forms derived from the old, carrying with

it this accumulated store.

While it was

in the previous form, it played through it, adapting it to express each newly

awakened energy; the form hands on these adaptations, inwrought into its

substance, to the separated part of itself that we speak of as its offspring,

which, beings of its substance, must needs have the peculiarities of that

substance; the life pours itself into that offspring with all its awakened

powers, and moulds it yet further ; and so on and on.

Modern

science is proving more and more clearly that heredity plays an ever-decreasing

part in the evolution of the higher creatures, that mental and moral qualities

are not transmitted from parents to offspring, and that the higher qualities

the more patent is this fact ‘ the child of the genius is oft-times a dolt;

commonplace parents give birth to a genius.

A continuing

substratum there must be, in which mental and moral qualities inhere, in order

that they may increase, else would Nature, in this most important department of

her work, show erratic uncaused production instead of orderly continuity. On

this science is dumb, but the Ancient Wisdom teaches that this continuing

substratum is the Monad, which is the receptacle of all results, the storehouse

in which all experiences are garnered as increasingly active powers.

These two

principles firmly grasped – of the Monad with potentialities becoming powers,

and of the continuity of the life form – we can proceed to the continuity of

life and form – we can proceed to study their working out in detail, and we

shall find that they solve many of the perplexing problems of modern science,

as well as the yet more heart-searching problems confronted by the

philanthropist and the sage.

Let us start

by considering the monad as it is first subjected to the impacts from the

formless levels of the mental plane, the very beginning of the evolution of

form. Its first faint responsive thrillings draw round it some of the matter of

that plane, and we have the gradual evolution of the first elemental kingdom,

already mentioned. (See chapter IV, on "The Mental Plane").

The great

fundamental types of the Monad are seven in number, sometimes imaged as like

the seven colours of the solar spectrum, derived from the three primary.

("As above, so below." We instinctively remember the three LOGOI and

the seven primeval Sons of the Fire ; in Christian Symbolism, the Trinity and the

"Seven Spirits that are before the throne" ; or in Zoroastrian,

Ahuramazda and the seven Ameshaspentas.)

Each of these

types has its own colouring of characteristics, and this colouring persists

throughout the aeonian cycle of its evolution, affecting all the series of

living things that are animated by it. Now begins the process of subdivision in

each of these types, that will be carried on, subdividing and ever subdividing,

until the individual is reached.

The currents

set up by the commencing outward-going energies of the Monad – to follow one

line of evolution will suffice ; the other six are like unto it in principle –

have but brief form-life, yet whatever experience can be gained through them is

represented by an increasedly responsive life in the Monad who is their source

and cause ; as this responsive life consists of vibrations that are often

incongruous with each other, a tendency towards separation is set up within the

Monad, the harmoniously vibrating forces grouping themselves together for, as

it were, concerted action, until various sub-Monads, if the epithet may for a

moment be allowed, are formed, alike in their main characteristics, but

differing in details, like shades of the same colour.

These become,

by impacts from the lower levels of the mental plane, the Monads of the second

elemental kingdom, belonging to the form region of that plane, and the process

continues, the Monad ever adding to its power to respond, each Monad being the

inspiring life of countless forms, through which it receives vibrations, and,

as the forms disintegrate, constantly vivifying new forms ; the process of

subdivision also continues from the cause already described.

Each Monad

thus continually incarnates itself in forms, and garners within itself as awakened

powers all the results obtained through the forms it animates. We may well

regard these Monads as the souls of groups of forms; and as evolution proceeds,

these forms show more and more attributes, the attributes being the powers of

the monadic group-soul manifested through the forms in which it is incarnated.

The

innumerable sub-Monads of this second elemental kingdom presently reach a stage

of evolution at which they begin to respond to the vibrations of astral matter,

and they begin to act on the astral plane, becoming the Monads of the third

elemental kingdom, and repeating in this grosser world all the processes

already accomplished on the mental plane.

They become

more and more numerous as monadic group-souls, showing more and more diversity in

detail, the number of forms animated by each becoming less as the specialised

characteristics become more and more marked.

Meanwhile, it

may be said in passing, the ever-flowing stream of life from the LOGOS supplies

new Monads of form on the higher levels, so that the evolution proceeds

continuously, and as the more-evolved Monads incarnate in the lower worlds

their place is taken by the newly emerged Monads in the higher.

By this

ever-repeated process of the reincarnation of the Monads, or Monadic group-soul,

in the astral world, their evolution proceeds, until they are ready to respond

to the impacts upon them from physical matter. When we remember that the

ultimate atoms of each plane have their sphere-walls composed of the coarsest

matter of the plane immediately above it, it is easy to see how the Monads

become responsive to impacts from one plane after another.

When, in the

first elemental kingdom, the Monad had become accustomed to thrill responsively

to the impacts of matter of that plane, it would soon begin to answer to

vibrations received through the coarsest forms of that matter from the matter

of the plane next below. So, in its coatings of matter that were the

forms

composed of the coarsest materials of the material plane, it would become

susceptible to vibrations of astral atomic matter ; and, when incarnated in

forms of the coarsest astral matter, it would similarly become responsive to

atomic physical ether, the sphere-walls of which are constituted of the

grossest astral materials.

Thus the

Monad may be regarded as reaching the physical plane ; and there it begins, or,

more accurately, all these monadic group-souls begin, to incarnate themselves

in filmy physical forms, the etheric doubles of the future dense minerals of

the physical world. Into these filmy forms the nature-spirits build

the denser

physical materials, and thus minerals of all kinds are formed, the most rigid

vehicles in which the evolving life in-closes itself, and through which the

least of its powers can express themselves. Each monadic group-soul has its own

mineral expressions, the mineral forms in which it is incarnated,

and the

specialisation has now reached a high degree. These Monadic group-souls are

sometimes called in their totality the mineral Monad or the Monad incarnating

in the mineral kingdom.

From this

time forward the awakened energies of the Monad play a less passive part in

evolution. They begin to seek expression actively to some extent when once

aroused into functioning, and to exercise a distinctly moulding influence

over the

forms in which they are imprisoned. As they become too active for their mineral

embodiment, the beginnings of the more plastic forms of the vegetable kingdom

manifest themselves, the nature-spirits aiding this evolution throughout the

physical kingdoms. In the mineral kingdom there had already been shown a

tendency towards the definite organisation of form, the laying down of certain

lines ( The axes of growth which determine form. They appear definitely in

crystals ) along which the growth proceeded. This tendency governs henceforth

all the building of forms, and is the cause of the exquisite symmetry of

natural

objects, with

which every observer is familiar.

The monadic

group-souls in the vegetable kingdom undergo division and subdivision with

increasing rapidity, in consequence of the still greater variety of impacts to

which they are subjected, the evolution of families, generations, and species

being due to this invisible subdivision.

When any

genus, with its generic monadic group-soul, is subjected to very varying

conditions, i.e., when the forms connected with it receive very different

impacts, a fresh tendency to subdivide is set up in the Monad, and various

species are evolved, each having its own specific group-soul.

When Nature

is left to her own working the process is slow, although the nature-spirits do

much towards the differentiation of species ; but when man has been evolved,

and when he begins his artificial systems of cultivation, encouraging the play

of one set of forces, warding off another, then this differentiation can be

brought about with considerable rapidity, and specific

differences

are readily evolved. So long as actual division has not taken place in the

monadic group-soul, the subjection of the forms to similar influences may again

eradicate the separative tendency, but when that division is completed the new

species are definitely and firmly established , and are ready to send out

offshoots of

their own.

In some of

the longer-lived members of the vegetable kingdom the element of personality

begins to manifest itself, the stability of the organism rendering possible

this foreshadowing of individuality. With a tree, living for scores of years,

the recurrence of similar conditions causing similar impacts, the seasons ever

returning year after year, the consecutive motions caused by them, the rising

of the sap, the putting forth of leaves, the touches of the wind, of the

sunbeams, of the rain – all these outer influences with their rhythmical

progression – set up responsive thrillings in the monadic group-soul, and, as

the sequence

impresses itself by continual repetition, the recurrence of one leads to the

dim expectation of its oft-repeated successor. Nature evolves no quality

suddenly, and these are the first faint adumbrations of what will later be

memory and anticipation.

In the

vegetable kingdom also appear the foreshadowings of sensation, evolving in its

higher members to what the Western psychologist would term "massive"

sensations of pleasure and discomfort. (The "massive" sensation is

one that pervades the organism and is not felt especially in any one part more

than in

others. It is

the antithesis of the "acute.") It must be remembered that the Monad

has drawn round itself materials of the planes through which it has descended,

and hence is able to contact impacts, from those planes, the strongest and

those most nearly allied to the grossest forms of matter being the first to

make themselves felt.

Sunshine and

the chill of its absence at last impress themselves on the monadic

consciousness ; and its astral coating, thrown into faint vibrations, gives

rise to the slight massive kind of sensation spoken of. Rain and drought

affecting the mechanical constitution of the form, and its power to convey

vibrations to

the ensouling

Monad – are another of the "pairs of opposites," the play of which

arouses the recognition of difference, which is the root alike of all

sensation, and later of all thought. Thus by their repeated plant-reincarnations

the monadic group-souls in the vegetable kingdom evolve, until those that

ensoul the highest members of the kingdom are ready for the next step.

This step

carries them into the animal kingdom, and here they slowly evolve in their physical

and astral vehicles a very distinct personality. The animal, being free to move

about, subjects itself to a greater variety of conditions than can be

experienced by the plant, rooted to a single spot, and this variety, as ever,

promotes differentiation.

The monadic

group-soul, however, which animates a number of wild animals of the same

species or subspecies, while it receives a great variety of impacts, since they

are for the most part repeated continually and are shared by all the members of

the group, differentiates but slowly.

These impacts

aid in the development of the physical and astral bodies, and through them the

monadic group-soul gathers much experience. When the form of a member of the

group perishes, the experience gathered through that form is accumulated in the

monadic group-soul, and may be said to colour it ; the slightly increased life

of the monadic group-soul, poured into all the forms which compose its group,

shares among all the experiences of the perished form, and in this way

continually repeated experiences, stored up in the monadic group-soul, appear

as instincts, "accumulated hereditary experiences" in the new forms.

Countless

birds having fallen a prey to hawks, chicks just out of the egg will cower at

the approach of one of the hereditary enemies, for the life that is incarnated

in them knows the danger, and the innate instinct is the expression of its

knowledge. In this way are formed the wonderful instincts that guard animals

from innumerable habitual perils, while a new danger finds them

unprepared

and only bewilders them.

As animals

come under the influence of man, the monadic group-souls evolves with greatly

increased rapidity, and, from causes similar to those which affect plants under

domestication, subdivision of the incarnating life is more readily brought

about. Personality evolves and becomes more and more strongly marked ; in the

earlier stages it may almost be said to be compound – a whole flock of wild

creatures will act as though moved by a single personality, so completely are

the forms dominated by the common soul, it, in turn, being affected by the

impulse from the external world.

Domesticated

animals of the higher types, the elephants, the horse, the cat, the dog, show a

more individualised personality – two dogs, for instance, may act very

differently under the impact of the same circumstances. The monadic group-soul

incarnates in a decreasing number of forms as it gradually approaches the point

at which complete individualisation will be reached. The desire-body, or Kâmic

vehicle, becomes considerably developed, and persists for some time after the

death of the physical body, leading an independent existence in Kâmaloka. At

last the decreasing number of forms animated by a monadic group-soul comes down

to unity, and it animates a succession of single forms – a condition differing

from human reincarnation only by the absence of Manas, with its causal and

mental bodies.

The mental

matter brought down by the monadic group-souls begins to be susceptible to

impacts from the mental plane, and the animal is then ready to receive the

third great outpouring of the life of the LOGOS – the tabernacle is ready for

the reception of the human Monad.

The human

Monad is, as we have seen, triple in its nature, its three aspects being

denominated, respectively, the Spirit, the spiritual Soul, and the human Soul,

Âtma-Buddhi-Manas. Doubtless, in the course of eons of evolution, the upwardly

evolving Monad of form might have unfolded Manas by progressive growth, but both

in the human race in the past, and in the animals of the present, such has not

been the course of Nature.

When the

house was ready the tenant was sent down ; from the higher planes of being the

âtmic life descended, veiling itself in Buddhi, as a golden thread ; and its

third aspect, Manas, showing itself in the higher levels of the formless world

of the mental plane, germinal Manas within the form was fructified, and the

embryonic causal body was formed by the union. This is the individualisation of

the spirit, the incasing of it in form, and this spirit incased in the causal

body is the soul, the individual, the real man. This is his birth hour; for

though his essence be eternal, unborn and undying, his birth in time as an

individual is definite.

Further, this

outpoured life reaches the evolving forms not directly, but by intermediaries.

The human race having attained the point of receptivity, certain great Ones,

called Sons of Mind – (Manasaputra is the technical name, being merely the

Sanskrit for Sons of Mind.) – cast into men the monadic spark of

Âtma-Buddhi-Manas,

needed for the formation of the embryonic soul.

And some of

these great Ones actually incarnated in human forms, in order to become the

guides and teachers of infant humanity. These Sons of Mind had completed Their

own intellectual evolution in other worlds, and came to this

younger

world, our earth, for the purpose of thus aiding in the evolution of the human

race. They are in truth, the spiritual fathers of the bulk of our humanity.

Other intelligences of much lower grade, men who had evolved in preceding

cycles in another world, incarnated among the descendants of the race

that received

its infant souls in the way just described. As this race evolved, the human

tabernacles improved, and myriads of souls that were awaiting the opportunity

of incarnation, that they might continue their evolution, took birth among its

children.

These

partially evolved souls are also spoken of in the ancient records as Sons of

Mind, for they were possessed of mind, although comparatively it was but little

developed – childish souls we may call them, in distinguishment from the

embryonic

souls of the bulk of humanity, and the mature souls of the great Teachers.

These child-souls,

by reason of their more evolved intelligence, formed the leading types of the

ancient world, the classes higher in mentality, and therefore in the power of

acquiring knowledge, that dominated the masses of less developed men in

antiquity.

And thus

arose, in our world, the enormous differences in mental and moral capacity

which separate the most highly evolved

from the

least evolved races, and which, even within the limits of single race, separate

the lofty philosophic thinker from the well-nigh animal type of the most

depraved of his own nation. These differences are but differences of the stage

of evolution, of the age of the soul, and they have been found to exist

throughout the whole of history of humanity on this globe. Go back as far as we

may in

historic records, and we may find lofty intelligence and debased ignorance side

by side, and the occult records, carrying us backwards, tell a similar story of

the early millennia of humanity.

Nor should

this distress us, as though some had been unduly favoured and others unduly

burdened for the struggle of life. The loftiest soul had its childhood and its

infancy, albeit in previous worlds, where other souls were as high above it as

others are below it now ; the lowest soul shall climb to where our highest are

standing, and souls yet unborn shall occupy its present place in evolution.

Things seem

unjust because we wrench our world out of its place in evolution, and set it

apart in isolation, with no forerunners and no successors. It is our ignorance

that sees the injustice ; the ways of Nature are equal, and she brings to all

her children infancy, childhood, and manhood. Nor hers the fault if our

folly demands

that all souls shall occupy the same stage of evolution at the same time, and

cries "Unjust!" if the demand be not fulfilled.

We shall best

understand the evolution of the soul, if we take it up at the point where we

left it, when animal-man was ready to receive, and did receive, the embryonic

soul. To avoid a possible misapprehension, it may be well to say that there

were not henceforth two Monads in man – the one that had built the

human

tabernacle, and the one that descended into that tabernacle, and whose lowest

aspect was the human soul.

To borrow a

simile again from H. P. Blavatsky, as two rays of the sun may pass through a

hole in a shutter, and mingling together form but one ray though they had been

twain, so is it with these rays from the Supreme Sun, the divine Lord

of our

universe. The second ray, as it entered into the human tabernacle, blended with

the first, merely adding to it fresh energy and brilliance, and the human

Monad, as a unit, began its mighty task of unfolding the higher powers in man

of that divine Life whence it came.

The embryonic

soul, the Thinker, had at the beginning for its embryonic mental body the

mind-stuff envelope that the Monad of form had brought with it, but had not yet

organised into any possibility of functioning. It was the mere germ of a mental

body, attached to a mere germ of a causal body, and for many a life the

strong

desire-nature had its will with the soul, whirling it along the road of its own

passions and appetites, and dashing up against it all the furious waves of its

own uncontrolled animality.

Repulsive as

this early life of the soul may at first seem to some when looked at from the

higher stage that we have now attained, it was a necessary one for the

germination of the seeds of mind. Recognition of difference, the perception

that one thing is different from another, is a preliminary essential to

thinking

at all. And,

in order to awaken this perception in the as yet unthinking soul, strong and

violent contrasts had to strike upon it, so as to force differences upon it –

blow after blow of riotous pleasure, blow after blow of crushing pain.

The external

world hammered on the soul through the desire nature, till perceptions began to

be slowly made, and, after countless repetitions, to be registered. The little

gains made in each life were stored up by the Thinker, as we have already seen,

and thus slow progress was made.

Slow

progress, indeed, for scarcely anything was thought, and hence scarcely

anything was done in the way of organising the mental body. Not until many

perceptions had been registered in it as mental images was there any material

on which mental action, initiated from within, could be based ; this would

begin

when two or

more of these mental images were drawn together, and some inference, however

elementary, was made from them. That inference was the beginning of reasoning,

the germ of all the systems of logic which the intellect of man has since

evolved or assimilated. These inferences would at first all be made in the

service of the desire-nature, for the increasing of pleasure, the lessening of

pain ; but each one would increase the activity of the mental body, and would

stimulate it into more ready functioning.

It will

readily be seen that at this period of his infancy man had no knowledge of good

or of evil; right and wrong for him had no existence. The right is that which

is in accordance with the divine will, which helps forward the progress of the

soul, which tends to the strengthening of the higher nature of man and to the

training and subjugation of the lower, the wrong is that which retards

evolution,

which retains the soul in the lower stages after he has learned the lessons

they have to teach, which tends to the mastery of the lower nature over the

higher, and assimilates man to the brute he should be outgrowing instead of to

the God he should be evolving.

Ere man could

know what was right, he had to learn the existence of the law, and this he

could only learn by following all that attracted him in the outer world, by

grasping every desirable object, and then by learning from experience, sweet

or bitter,

whether his delight was in harmony or in conflict with the law. Let us take an

obvious example, the taking of pleasant food, and see how infant man might

learn therefrom the presence of a natural law. At the first taking, his hunger

was appeased, his taste was gratified, and only pleasure resulted from the

experience, for his action was in harmony with law. On another occasion,

desiring to increase pleasure, he ate overmuch and suffered in consequence, for

he transgressed against the law. A confusing experience to the dawning

intelligence, how the pleasurable became painful by excess.

Over and over

again he would be led by desire into excess, and each time he would experience

the painful consequences, until at last he learned moderation, i.e., he learned

to conform his bodily acts in this respect to physical law; for he found that

there were conditions which affected him and which he could not control, and

that only by observing them could physical happiness be insured.

Similar

experiences flowed in upon him through all the bodily organs, with undeviating

regularity ; his outrushing desires brought him pleasure or pain just as they

worked with the laws of Nature or against them, and, as experience increased,

it began to guide his steps, to influence his choice, It was not as though he

had to begin his experience anew with every life, for on each new

birth he

brought with him mental faculties a little increased, and

ever-accumulating

store.

I have said

that the growth in these early days was very slow, for there was but the

dawning of mental action, and when the man left his physical body at death he

passed most of his time in Kâmaloka, sleeping through a brief devachanic period of

unconscious assimilation of any minute mental experience not yet sufficiently

developed for the active heavenly life that lay before him after many days.

Still, the

enduring causal body was there, to be the receptacle of his qualities, and to

carry them on for further development into his next life on earth. The part

played by the monadic group-soul in the earlier stages of evolution is played

in man by the causal body, and it is this continuing entity who, in all cases,

makes evolution possible. Without him, the accumulation of mental and moral

experiences, shown as faculties, would be as impossible as

would be the

accumulation of physical experiences, shown as racial and family

characteristics without the continuity of physical plasm.

Souls without

a past behind them, springing suddenly into existence, out of nothing, with

marked mental and moral peculiarities, are a conception as monstrous as would

be the corresponding conception of babies suddenly appearing from nowhere,

unrelated to anybody, but showing marked racial and family types.

Neither man

nor his physical vehicle is uncaused, or caused by the direct power of the

LOGOS ; here, as in so many other cases, the invisible things are clearly seen

by their analogy with the visible, the visible being, in very truth, nothing

more than the images, the reflections, of things unseen.

Without a

continuity in the physical plasm, there would be no means for the evolution of

physical peculiarities ; without the continuity of the intelligence, there

would be no means for the evolution of mental and moral qualities. In both

cases, without continuity, evolution would be stopped at its first stage, and

the world would be a chaos of infinite and isolated beginnings instead of a

cosmos continually becoming.

We must not

omit to notice that in these early days much variety is caused in the type and

in the nature of individual progress by the environment which surrounds the

individual. Ultimately all the souls have to develop all their powers, but the

order in which these powers are developed depends on the circumstances amid

which the soul is placed. Climate, the fertility or sterility of nature, the

life of the mountain or of the plain, of the inland forest or the ocean shore –

these things and countless others will call into activity one set or another of

the awakening mental energies.

A life of

extreme hardship, of ceaseless struggle with nature, will develop very

different powers from those evolved amid the luxuriant plenty of a tropical

island ; both sets of powers are needed, for the soul is to conquer every

region of nature, but striking differences may thus be evolved even in souls of

the same age, and one may appear to be more advanced than the other, according

as the observer estimates most highly the more "practical" or the

more

"contemplative"

powers of the soul, the active outward-going energies, or the quiet

inward-turned musing faculties. The perfected soul possesses all, but the soul

in the making must develop them successively, and thus arises another cause of

the immense variety found among human beings.

For again, it

must be remembered that human evolution is individual. In a group informed by a

single monadic group-soul the same instincts will be found in all, for the

receptacle of the experiences is that monadic group-soul, and it pours its life

into all forms dependent upon it.

But each man

has his own physical vehicle and one only at a time, and the receptacle of all

experiences is the causal body, which pours its life into its one physical

vehicle, and can affect no other physical vehicle, being connected with none

other. Hence we find differences separating individual men greater, than the ever

separated, closely allied animals, and hence also the evolution of qualities

cannot be studied in men in the mass, but only in the continuing individual.

The lack of power to make such a study leaves science unable to explain why

some men tower above their fellows, intellectual and moral giants, unable to

trace the intellectual evolution of a Shankarâchârya or a Pythagoras, the moral

evolution of a Buddha or of a Christ.

Let us now

consider the factors in reincarnation, as a clear understanding of these is

necessary for the explanation of some of the difficulties – such as the alleged

loss of memory – which are felt by those unfamiliar with the idea. We have seen

that man, during his passage through physical death, Kâmaloka and Devachan, loses one after

the other, his various bodies, the physical, the astral, and the mental. These

are all disintegrated, and their particles remix with the materials of their

several planes. The connection of the man with the physical vehicle is entirely

broken off and done with ; but the astral and mental bodies hand on to the man

himself, to the Thinker, the germs of the faculties and qualities resulting

from the activities of the earth-life, and these are stored within the causal

body, the seeds of his next astral and mental bodies.

At this

stage, then, only the man himself is left, the labourer who has brought his

harvest home, and has lived upon it till it is all worked up into himself. The

dawn of a new life begins, and he must go forth again to his labour until the

even.

The new life

begins by the vivifying of the mental germs, and they draw upon the materials

of the lower mental levels, till a mental body has grown up from them that

represents exactly the mental stage of the man, expressing all his mental

faculties as organs ; the experiences of the past do not exist as mental images

in this new body; as mental images they perished when the old mind-body

perished, and only their essence, their effects on faculty, remain ; they were

the food of the mind, the materials which it wove into powers, and in the new

body they reappear as powers, they determine its materials, and they form its

organs. When the man, the Thinker, has thus clothed himself with a new body for

his coming life on the lower mental levels, he proceeds, by vivifying the

astral germs, to provide himself with an astral body for his life on the astral

plane.

This, again,

exactly represents his desire-nature, faithfully reproducing the qualities he

evolved in the past, as the seed reproduces its parent tree. Thus the man

stands, fully equipped for his next incarnation, the only memory of these

events of his past being in the causal body, in his own enduring form, the one

body that passes on from life to life.

Meanwhile,

action external to himself is being taken to provide him with a physical body

suitable for the expression of his qualities. In past lives he has made ties

with, contracted liabilities towards, other human beings, and some of these

will partly determine his place of birth and his family. – ( This and the

following causes determining the outward circumstances of the new life will be

fully explained in Chapter IX, on "Karma".) He has been a source of

happiness or of unhappiness to others ; this is a factor in determining the

conditions of his coming life. His desire-nature is well disciplined, or

unregulated and riotous ; this will be taken into account in the physical

heredity of the new body. He has cultivated certain mental powers, such as the

artistic ; this must be considered, as here again physical heredity is an

important factor where delicacy of nervous organisation and tactile sensibility

are required.

And so on, in

endless variety. The man may, certainly will, have in him many incongruous

characteristics, so that only some can find expression in any one body that

could be provided, and a group of his powers suitable for simultaneous

expression must be selected. All this is done by certain mighty spiritual

Intelligences,( Spoken of by H.P.Blavatsky in the Secret Doctrine. They are the

Lipika, the Keepers of the kârmic records, and the Mahârâjas, who direct the

practical working out of the decrees of the Lipika.) - often spoken of as the

Lords of Karma, because it is their function to superintend the working out of

causes continually set going by thoughts, desires, and actions. They hold the

threads of destiny which each man has woven, and guide the reincarnating man to

the environment determined by his past, unconsciously self-chosen through his

past life.

The race, the

nation, the family, being thus determined, what may be called the mould of the

physical body – suitable for the expression of the man’s qualities, and for the

working out of the causes he has set going – is given by these great Ones, and

the new etheric double, a copy of this, is built within the mother’s womb by

the agency of an elemental, the thought of the Karmic Lords being its motive

power.

The dense

body is built into the etheric double molecule by molecule, following it

exactly, and here physical heredity has full sway in the materials provided.

Further, the

thoughts and passions of surrounding people, especially of the continually

present father and mother, influence the building elemental in its work, the

individuals with whom the incarnating man had formed ties in the past thus

affecting the physical conditions growing up for his new life on earth.

At a very

early stage the new astral body comes into connection with the new etheric

double, and exercises considerable influence over its formation, and through it

the mental body works upon the nervous organisation, preparing it to become a

suitable instrument for its own expression in the future. This influence

commenced in ante natal life – so that when a child is born its brain-formation

reveals the extent and balance of its mental and moral qualities – is continued

after birth, and this building of brain and nerves, and their correlation to

the astral and mental bodies, go on till the seventh year of childhood, at

which age the connection between the man and his physical vehicle is complete,

and he may be said to work through it henceforth more than upon it.

Up to this

age, the consciousness of the Thinker is more upon the astral plane than upon

the physical, and this is often evidenced by the play of psychic faculties in

young children. They see invisible comrades and fairy landscapes, hear voices

inaudible to their elders, catch charming and delicate fancies from

the astral

world. These phenomena generally vanish as the Thinker begins to work

effectively through the physical vehicle, and the dreamy child becomes the

commonplace boy or girl, oftentimes much to the relief of the bewildered

parents, ignorant of the cause of their child’s "queerness."

Most children

have at least a touch of this "queerness," but they quickly learn to

hide away their fancies and visions from their unsympathetic elders, fearful of

blame for "telling stories," or of what the child dreads far more –

ridicule.

If parents

could see their children’s brains, vibrating under an inextricable mingling of

physical and astral impacts, which the children themselves are quite incapable

of separating, and receiving sometimes a thrill – so plastic are they – even

from the higher regions, giving a vision of ethereal beauty, of heroic

achievement,

they would be more patient with, more responsive to, the confused prattlings of

the little ones, trying to translate into the difficult medium of unaccustomed

words the elusive touches of which they are conscious, and which they try to

catch and retain. Reincarnation, believed in and understood, would relieve

child life of its most pathetic aspect, the unaided struggle of the soul to

gain control over its new vehicles, and to connect itself fully with its

densest body without losing power to impress the rarer ones in a way that would

enable them to convey to the denser their own more subtle vibrations.

The ascending

stages of consciousness through which the Thinker passes as he reincarnates during

his long cycle of lives in the three lower worlds are clearly marked out, and

the obvious necessity for many lives, in which to experience them, if he is to

evolve at all, may carry to the more thoughtful

minds the

clearest conviction of the truth of reincarnation.

The first of

the stages is that in which all the experiences are sensational, the only

contribution made by the mind consisting of the recognition that contact with

some object is followed by a sensation of pleasure, while contact with others

is followed by a sensation of pain. These objects form mental pictures, and the

pictures soon begin to act as a stimulus to seek the objects

associated

with pleasure, when those objects are not present, the germs of memory and of

mental initiative thus making their appearance. This first rough division of

the external world is followed by the more complex idea of the bearing of

quantity on pleasure and pain, already referred to.

At this stage

of evolution, memory is very short lived, or, in other words, mental images are

very transitory. The idea of forecasting the future from the past, even to the

most rudimentary extent, has not dawned on the infant Thinker,

and his

actions are guided from outside, by the impacts that reach him from the

external world, or at furthest by the promptings of his appetites and passions,

craving gratification. He will throw away anything for an immediate

satisfaction, however necessary the thing may be for his future well being; the

need of the moment overpowers every other consideration. Of human souls in

thisembryonic condition, numerous examples can be found in books of travel, and

the necessity for many lives will be impressed on the mind of any one who

studies the mental condition of the least evolved savages, and compares it with

the mental condition of even average humanity among ourselves.

Needless to

say that the moral capacity is no more evolved than the mental; the idea of

good and evil has not yet been conceived. Not is it possible to convey to the

quite undeveloped mind even elementary notion of either good or bad. Good and

pleasant are to it interchangeable terms, as in the well-known case of the

Australian savage mentioned by Charles Darwin. Pressed by hunger, the man

speared the nearest living creature that could serve as food, and this happened

to be his wife; a European remonstrated with him on the wickedness of his deed,

but failed to make any impression; for from the reproach that to eat his wife

was very, very bad he only deduced the inference that the stranger thought she

had proved nasty of indigestible, and he put him right by smiling peacefully as

he patted himself after his meal, and declaring in a satisfied way, "She

is very good."

Measure in

thought the moral distance between that man and St. Francis of Assisi, and it

will be seen that there must either be evolution of souls as there is evolution

of bodies, or else in the realm of the soul there must be constant miracle,

dislocated creations.

There are two

paths along either of which man may gradually emerge from this embryonic mental

condition. He may be directly ruled and controlled by men far more evolved than

himself, or he may be left slowly to grow unaided. The latter case would imply

the passage of uncounted millennia, for, without example and without

discipline, left to the changing impacts of external objects, and to friction

with other men as undeveloped as himself, the inner energies could be but very

slowly aroused.

As a matter

of fact, man has evolved by the road of direct precept and example and of

enforced discipline. We have already seen that when the bulk of the average

humanity received the spark which brought the Thinker into being, there were

some of the greater Sons if Mind who incarnated as Teachers, and that there was

also a long succession of lesser Sons of Mind, at various stages of evolution,

who came into incarnation as the crest-wave of the advancing tide of humanity.

These ruled

the less evolved, under the beneficent sway of the great Teachers, and the

compelled obedience to elementary rules of right living – very elementary at

first, in truth – much hastened the development of mental and moral faculties

in the embryonic souls. Apart from all other records the gigantic remains of

civilizations that have long since disappeared – evidencing great engineering

skill, and intellectual conceptions far beyond anything possible by the mass of

the then infant humanity – suffice to prove that there were present on earth

men with minds that were capable of greatly planning and greatly executing.

Let us

continue the early stage of the evolution of consciousness. Sensation was

wholly lord of the mind, and the earliest mental efforts were stimulated by

desire. This led the man, slowly and clumsily, to forecast, to plan. He began

to recognise a definite association of certain mental images, and, when one

appeared, to

expect the appearance of the other that had invariably followed in its wake. He

began to draw inferences, and even to initiate action on the faith of these

inferences – a great advance. And he began also to hesitate now and

again to

follow the vehement promptings of desire, when he found, over and over again,

that the gratification demanded was associated in his mind with the subsequent

happening of suffering.

This action

was much quickened by the pressure upon him of verbally expressed laws; he was

forbidden to seize certain gratifications, and was told that suffering would

follow disobedience. When he had seized the delight-giving

object and

found the suffering follow upon pleasure, the fulfilled declaration made a far

stronger impression on his mind than would have been made by the unexpected –

and therefore to him fortuitous – happening of the same thing un foretold. Thus

conflict continually arose between memory and desire, and the

mind grew

more active by the conflict, and was stirred into livelier functioning. The

conflict, in fact, marked the transition to the second great stage.

Here began to

show itself the germ of will. Desire and will guide a man’s actions, and will

has even been defined as the desire which emerges triumphant from the contest

of desires. But this is a crude and superficial view, explaining nothing.

Desire is the outgoing energy of the Thinker, determined in its direction by

the attraction of external objects. Will is the outgoing energy

of the

Thinker, determined in its direction by the conclusions drawn by the reason,

from past experiences, or by the direct intuition of the Thinker himself.

Otherwise put: desire is guided from without – will from within. At the

beginning of man’s evolution, desire has complete sovereignty, and hurries him

hither and

thither; in the middle of his evolution, desire and will are in continual conflict,

and victory lies sometimes with the one, sometimes with the other; at the end

of his evolution desire has died, and will rules with unopposed, unchallenged

sway.

Until the

Thinker, is sufficiently developed to see directly, will is guided by him

through the reason; and as the reason can draw its conclusions only from its

stock of mental images – its experiences – and that stock is limited, the will

constantly commands mistaken actions. The suffering which flows from these

mistaken actions increases the stock of mental images, and thus gives the

reason an increased store from which to draw its conclusions. Thus progress is

made and wisdom is born.

Desire often

mixes itself up with will, so that what appears to be determined from within is

really largely prompted by the cravings of the lower nature for objects which

afford it gratification. Instead of an open conflict between the

two, the

lower subtly insinuates itself into the current of the higher and turns its

course aside. Defeated in the open field, the desire of the personality thus

conspire against their conqueror, and often win by guile what they failed to

win by force. During the whole of this second great stage, in which the

faculties of

the lower

mind are in full course of evolution, conflict is the normal condition,

conflict between the rule of sensations and the rule of reason.

The problem

to be solved in humanity is the putting an end to conflict while preserving the

freedom of the will; to determine the will inevitably to the best, while yet

leaving that best as a matter of choice. The best is to be chosen, but by a

self-initiated volition, that shall come with all the certainty of a

foreordained necessity. The certainty of a compelling law is to be obtained

from

countless wills, each one left free to determine its own course.

The solution

of that problem is simple when it is known, though the contradiction looks

irreconcilable when first presented. Let man be left free to choose his own

actions, but let every action bring about an inevitable result; let him run

loose amid all objects of desire and seize whatever he will, but let him have

all the

results of his choice, be they delightful or grievous. Presently he will freely

reject the objects whose possession ultimately causes him pain; he will no

longer desire them when he has experienced to the full that their possession

ends in sorrow.

Let him

struggle to hold the pleasure and avoid the pain, he will none the less be

ground between the stones of law, and the lesson will be repeated any number of

times found necessary; reincarnation offers us many lives as are needed by the

most sluggish learner. Slowly desire for an object that brings suffering in its

train will die, and when the thing offers itself in all its attractive glamour

it will be rejected, not by compulsion but by free choice.

It is no

longer desirable, it has lost its power. Thus with thing after thing; choice

more and more runs in harmony with law. "There are many roads of error;

the road of truth is one"; when all the paths of error have been trodden,

when all have been found to end in suffering, the choice to walk in the way of

truth is unswerving, because based on knowledge. The lower kingdoms work

harmoniously, compelled by law; man’s kingdom is a chaos of conflicting wills,

fighting against, rebelling against law; presently there evolves from it a

nobler unity, a harmonious choice of voluntary obedience, an obedience that,

being voluntary, based on knowledge and on memory of the results of

disobedience, is stable and can be drawn aside by no temptation. Ignorant,

inexperienced, man would always have been in danger of falling; as a God,

knowing good and evil by experience, his choice of the good is raised forever

beyond possibility of change.

Will in the

domain of morality is generally entitled conscience, and it is subject to the

same difficulties in this domain as in its other activities. So long as actions

are in question which have been done over and over again, of which the

consequences are familiar either to the reason or to the Thinker himself, the

conscience speaks quickly and firmly. But when unfamiliar problems arise as to

the working out of which experience is silent, conscience cannot speak with

certainty; it has but a hesitating answer from the reason, which can draw only

a doubtful inference, and the Thinker cannot speak if his experience does not

include the circumstances that have now arisen.

Hence

conscience often decides wrongly; that is, the will, failing clear direction

from either the reason or the intuition, guides action amiss. Nor can we leave

out of consideration the influences which play upon the mind from without, from

the thought-forms of others, of friends, of the family, of the community, of

the nation. (Chapter 11, "The Astral Plane.") These all surround and

penetrate the mind with their own atmosphere, distorting the appearance of

everything, and throwing all things our of proportion. Thus influenced, the

reason often does not even judge calmly from its own experience, but draws false

conclusions as it studies its materials through a distorting medium.

The evolution

of moral faculties is very largely stimulated by the affections, animal and

selfish as these are during the infancy of the Thinker. The laws of morality

are laid down by the enlightened reason, discerning the laws by which Nature

moves, and bringing human conduct into consonance with the Divine Will.

But the

impulse to obey these laws, when no outer force compels, has its roots in love,

in that hidden divinity in man which seeks to pour itself out to give itself to

others. Morality begins in the infant Thinker when he is first moved by love to

wife, to child, to friend, to do some action that serves the loved one without

any thought of gain to himself thereby. It is the first conquest over the lower

nature, the complete subjugation of which is the achievement of moral

perfection.

Hence the

importance of never killing out or striving to weaken, the affection, as is done

in many of the lower kinds of occultism. However impure and gross the

affections may be, they offer possibilities of moral evolution from which the

cold-hearted and self-isolated have shut themselves out. It is an easier task

to

purify than

to create love, and this is why "the sinners" have been said by great

Teachers to be nearer to the kingdom of heaven than the Pharisees and Scribes.

The third

great stage of consciousness sees the development of the higher intellectual

powers; the mind no longer dwells entirely on mental images obtained from

sensations, no longer reasons on purely concrete objects, nor is concerned with

the attributes which differentiate one from another. The Thinker having learned

clearly to discriminate between objects by dwelling upon their unlikenesses,

now begins to group them together by some attribute which appears in a number

of objects otherwise dissimilar and makes a link between them.

He draws out,

abstracts, his common attribute, and sets all objects that posses it, apart

from the rest which are without it; and in this way he evolves the power of

recognising identity amid diversity, a step toward the much later recognition

of the One underlying the man, he thus classifies all that is around him,

developing the synthetic faculty, and learning to construct as well as analyse.

Presently he takes another step, and conceives of the common property as an

idea, apart from all the objects in which it appears, and thus constructs a

higher kind of mental image of a concrete object – the image of an idea that

has no phenomenal existence in the worlds of form, but which exists on the

higher levels of the mental plane, and affords material on which the Thinker

himself can work.

The lower

mind reaches the abstract idea by reason, and in thus doing accomplishes its

loftiest flight, touching the threshold of the formless world, and dimly seeing

that which lies beyond. The Thinker sees these ideas, and lives among them

habitually, and when the power of abstract reasoning is developed and exercised

the Thinker is becoming effective in his own world, and is beginning his life

of active functioning in his own sphere.

Such men care

little for the life of the senses, care little for external observation, or for

mental application to images of external objects; their powers are indrawn, and

no longer rush outwards in the search for satisfaction.

They dwell

calmly within themselves, engrossed with the problems of philosophy, with the

deepest aspects of life and thought, seeking to understand causes rather than

troubling themselves with effects, and approaching nearer and nearer to the

recognition of the One that underlies all the diversities of external Nature.

In the fourth

stage of consciousness that One is seen, and with the transcending the barrier

set up by the intellect the consciousness spreads out to embrace the world,

seeing all things in itself and as parts of itself, and seeing itself as a ray

of the LOGOS, and therefore as one with Him. Where is then the Thinker?

He has become

Consciousness, and, while the spiritual Soul can at will use any of his lower

vehicles, he is no longer limited to their use, nor needs them for this full

and conscious life. Then is compulsory reincarnation over and the man has

destroyed death; he has verily achieved immortality. Then has he become "a

pillar in the temple of God and shall go out no more."

To complete

this part of our study, we need to understand the successive quickenings of the

vehicles of consciousness, the bringing them one by one into activity as the

harmonious instruments of the human Soul.

We have seen

that from the very beginning of his separate life the Thinker has possessed

coatings of mental, astral, etheric, and dense physical matter. These form the

media by which his life vibrates outwards, the bridge of consciousness, as we

may call it, along which all impulses from the Thinker may reach the dense

physical

body, all impacts from the outer world may reach him.

But this

general use of the successive bodies as parts of a connected whole is a very

different thing from the quickening of each in turn to serve as a distinct

vehicle of consciousness, independently of those below it, and it is this

quickening of the vehicles that we have now to consider. The lowest vehicle,

the

dense

physical body, is the first one to be brought into harmonious working order;

the brain and the nervous system have to be elaborated and to be rendered

delicately responsive to every thrill which is within their gamut of vibratory

power. In the early stages, while the physical dense body is composed of the

grosser kinds of matter, this gamut is extremely limited, and the physical

organ of the mind can respond only to the slowest vibrations sent down.

It answers

far more promptly, as is natural, to the impacts from the external world caused

by objects similar in materials to itself. Its quickening as a vehicle of

consciousness consists in its being made responsive to the vibrations that are

initiated from within, and the rapidity of this quickening depends on the

co-operation of the lower nature with the higher, its loyal subordination of

itself in the service of its inner ruler.

When after

many, many life-periods, it dawns upon the lower nature that it exists for the

sake of the soul, that all its value depends on the help it can bring to the

soul, that it can win immortality only by merging itself in the soul, then its

evolution proceeds in giant strides. Before this, the evolution has been

unconscious; at first, the gratification of the lower nature was the object of

life, and, while this was a necessary preliminary for calling out the energies

of the Thinker, it did nothing directly to render the body a vehicle of

consciousness; the direct working upon it begins when the life of the man

establishes its centre in the mental body, and when thought commences to

dominate sensation.

The exercise

of the mental powers works on the brain and the nervous system, and the coarser

materials are gradually expelled to make room for the finer, which can vibrate in

unison with the thought-vibrations sent to them. The brain becomes finer in

constitution, and increases by ever more complicated

convolutions

the amount of surface available for the coating of nervous matter adapted to

respond to thought-vibrations. The nervous system becomes more delicately

balanced, more sensitive, more alive to every thrill of mental activity. And

when the recognition of its function as an instrument of the Soul,

spoken of

above, has come, then active co-operation in performing this function sets in.

The personality begins deliberately to discipline itself, and to set the

permanent interests of the immortal individual above its own transient

gratifications.

It yields up

the time that might be spent in the pursuit of lower pleasures to the evolution

of mental powers; day by day time is set apart for serious study; the brain is

gladly surrendered to receive impacts from within instead of from without, is

trained to answer to consecutive thinking, and is taught to refrain

from throwing

up its own useless disjointed images, made by past impressions.

It is taught

to remain at rest when it is not wanted by its master; to answer, not to

initiate vibrations. (One of the signs that it is being accomplished is the

cessation of the confused jumble of fragmentary images which are set up during

sleep by the independent activity of the physical brain. When the brain is

coming under

control this kind of dream is very seldom experienced.)

Further, some

discretion and discrimination will be used as to the food-stuffs which supply

physical materials to the brain. The use of the coarser kinds will be

discontinued, such as animal flesh and blood and alcohol, and pure food will

build up a pure body. Gradually the lower vibrations will find no materials

capable of

responding to them, and the physical body thus becomes more and more entirely a

vehicle of consciousness, delicately responsive to all the thrills of thought

and keenly sensitive to the vibrations sent outwards by the Thinker.

The etheric double

so closely follows the constitution of the dense body that it is not necessary

to study separately its purification and quickening; it does not normally serve

as a separate vehicle of consciousness, but works synchronously with its dense

partner, and when separated from it either by accident or by death, it responds

very feebly to the vibrations initiated from

within. It

function in truth is not to serve as a vehicle of mental-consciousness, but as

a vehicle of Prâna, of specialised life-force, and its dislocation from the

denser particles to which it conveys the life-currents is therefore disturbing

and mischievous.

The astral

body is the second vehicle of consciousness to be vivified, and we have already

seen the changes through which it passes as it becomes organised for the work.

(see Chapter II, "The Astral Plane".). When it is thoroughly

organised, the consciousness which has hitherto worked within it, imprisoned by

it, when in sleep it has left the physical body and is drifting about in the astral

world, begins not only to receive the impressions through it of astral objects

that form the so-called dream-consciousness, but also to perceive astral

objects by its senses – that is, begins to relate the impressions received to

the objects

which give rise to those impressions.

These

perceptions are at first confused, just as are the perceptions at first made by

the mind through a new physical baby-body, and they have to be corrected by

experience in the one case as in the other. The Thinker has gradually to

discover the new powers which he can use through this subtler vehicle, and by

which he can control the astral elements and defend himself against astral

dangers. He is not left alone to face this new world unaided, but is taught and

helped and – until he can guard himself – protected by those who are more

experienced than himself in the ways of the astral world. Gradually the new

vehicle of

consciousness comes completely under his control, and life on the astral plane

is as natural and as familiar as life on the physical.

The third

vehicle of consciousness, the mental body, is rarely, if ever, vivified for

independent action without the direct instruction of a teacher, and its

functioning belongs to the life of the disciple at the present stage of human

evolution. (See Chapter XI, "Man’s Ascent"). As we have already seen,

it is rearranged for separate functioning (See Chapter IV, "The Mental

Plane"), on the mental plane, and here again experience and training are

needed ere it comes fully under its owner’s control. A fact – common to all

these three vehicles of consciousness, but more apt to mislead perhaps in the

subtler than in the denser, because it is generally forgotten in their case,

while it is so obvious that it is remembered in the denser – is that they are

subject to evolution, and that with their higher evolution their powers to

receive and to respond to vibrations increase.

How many more

shades of a colour are seen by a trained eye than by an untrained. How many

overtones are heard by a trained ear, where the untrained hears only the single

fundamental note. As the physical senses grow more keen the world becomes

fuller and fuller, and where the peasant is conscious only his furrow and his

plough, the cultured mind is conscious of hedgerow flower and quivering aspen,

of rapturous melody down-dropping from the skylark and the whirring of tiny

wings through the adjoining wood, of the scudding of rabbits under the curled

fronds of the bracken, and the squirrels playing with each other through the

branches of the beeches, of all the gracious movements of wild things, of all

the fragrant odours of filed and woodland, of all the changing glories of the

cloud-flecked sky, and of all the chasing lights and shadows on the hills. Both

the peasant and the cultured have eyes, both have brains, but of what differing

powers of observation, of what differing powers to receive impressions.

Thus also in

other worlds. As the as the astral and mental bodies begin to function as

separate vehicles of consciousness, they are in, as it were, the peasant stage

of receptivity, and only fragments of the astral and mental worlds, with their

strange and elusive phenomena, make their way into consciousness; but they

evolve rapidly, embracing more and more, and conveying to consciousness a more

and more accurate reflection of its environment. Here, as everywhere else, we

have to remember that our knowledge is not the limit of Nature’s powers, and

that in the astral and mental worlds, as in the physical, we are still

children, picking up a few shells cast up by the waves, while the treasures hid

in the ocean are still unexplored.

The

quickening of the causal body as a vehicle of consciousness follows in due course

the quickening of the mental body, and opens up to a man a yet more marvelous

state of consciousness, stretching backwards into an illimitable past, onwards

into the reaches of the future. Then the Thinker not only possesses the

memory of his

own past and can trace his growth through the long succession of his incarnate

and excarnate lives, but he can also roam at will through the storied past of

the earth, and learn the weighty lessons of world-experience, studying the

hidden laws that guide evolution and the deep secrets of life hidden in the

bosom of Nature.

In that lofty

vehicle of consciousness he can each the veiled Isis, and lift a corner of her

down-dropped veil; for there he can face her eyes without being blinded by her

lightening glances, and he can see in the radiance that flows from her the

causes of the world’s sorrow and its ending, with heart pitiful and

compassionate,

but no longer wrung with helpless pain. Strength and calm and wisdom come to

those who are using the causal body as a vehicle of consciousness, and who

behold with opened eyes the glory of the Good law.

When the

buddhic body is quickened as a vehicle of consciousness the man enters into the

bliss of non-separateness, and knows in full and vivid realisation his unity with

all that is.

As the

predominant element of consciousness in the causal body is knowledge, and

ultimately wisdom, so the predominant element of consciousness in the buddhic

body is bliss and love.

The serenity

of wisdom chiefly marks the one, while the tenderest compassion streams forth

inexhaustibly from the other; when to these is added the godlike and unruffled

strength that marks the functioning of Âtma, then humanity is crowned with

divinity, and the God-man is manifest in all the plenitude of his power, of his

wisdom, of his love.

The handing

down to the lower vehicles of such part of the consciousness belonging to the

higher as they are able to receive does not immediately follow on the